A Layered Guide to Research Methodology

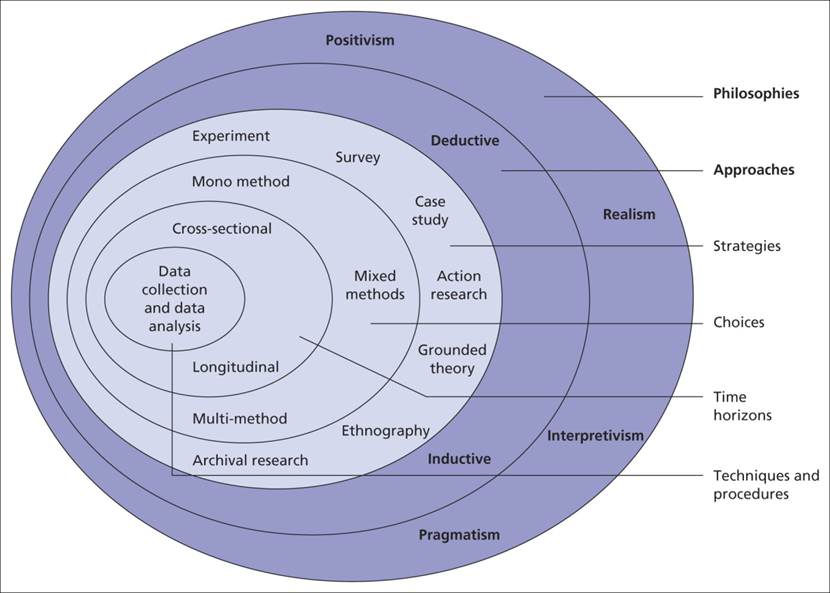

The process of designing a sound research methodology can be daunting, especially for early-stage researchers or students embarking on dissertations and theses. One of the most widely used frameworks to guide methodological decisions is the Research Onion, developed by Saunders, Lewis, and Thornhill (2007). This conceptual model offers a structured, multi-layered approach to developing a coherent research strategy, allowing researchers to peel back each methodological layer in a logical progression—much like peeling the layers of an onion. From philosophical underpinnings to practical data collection techniques, each layer of the onion informs the next, helping researchers build a robust foundation for their empirical investigations.

Research Philosophy: Establishing the Ontological and Epistemological Ground

At the outermost layer of the Research Onion is research philosophy, which refers to the researcher’s worldview about the nature of reality (ontology) and how knowledge is acquired (epistemology). The choice of philosophy significantly influences the entire research design, including the approach, strategy, and methods.

Positivism is grounded in the belief that reality is objective, measurable, and independent of human interpretation. It is closely aligned with natural sciences and typically involves hypothesis testing, using structured methodologies and quantitative data. Researchers operating under a positivist paradigm remain detached and neutral, ensuring that their values do not influence the outcomes.

In contrast, interpretivism suggests that reality is socially constructed and best understood through the subjective experiences of individuals. This philosophy is often adopted in social science research and favors qualitative methods such as interviews and observations. Interpretivist researchers aim to uncover meanings and understand phenomena in context, acknowledging their interaction with the research process.

Realism, another philosophical stance, shares similarities with both positivism and interpretivism. While it accepts that a reality exists independent of human perception, it also acknowledges that our understanding of this reality is inevitably shaped by social, cultural, and historical contexts. Realism is often divided into direct realism and critical realism—the latter emphasizing the need to interpret underlying mechanisms and structures that may not be directly observable.

Finally, pragmatism offers a more flexible philosophical orientation, focusing on what works in practice to solve real-world problems. Pragmatist researchers are not committed to a single philosophical position; instead, they choose approaches and methods that best suit the research objectives. This philosophy often supports the use of mixed methods, allowing for both quantitative and qualitative data.

Research Approach: The Logic of Knowledge Development

Nested within philosophy is the research approach, which dictates the reasoning used to generate and validate knowledge. The two primary approaches are deductive and inductive, with a third—abductive—gaining increasing relevance.

A deductive approach begins with established theory or hypotheses and tests them through empirical observation. This approach is typically associated with positivism and quantitative research. Deductive reasoning moves from the general to the specific, and the findings either confirm or refute the hypothesis. When a substantial body of existing literature informs the research problem, people commonly use it.

Conversely, an inductive approach involves collecting data first and then developing theories or patterns based on the data. It is closely linked with interpretivist philosophy and qualitative research. Induction moves from specific observations to broader generalizations and theories, making it ideal for exploring new or under-researched phenomena.

The abductive approach blends aspects of both deduction and induction. It is particularly useful when unexpected findings emerge during the research process. Abductive reasoning allows researchers to iterate between theory and data, refining their understanding and forming new theoretical insights that are grounded in empirical reality.

Research Strategy: The Blueprint for Inquiry

The research strategy forms the third layer of the Research Onion and refers to the overall plan that guides how the research question will be addressed. The choice of strategy must align with both the philosophical stance and the research approach.

Several strategies are available to researchers, each suited to different types of inquiries. Experiments are common in natural and behavioral sciences and involve manipulating variables under controlled conditions to examine causal relationships. Surveys are widely used in social research and involve collecting quantitative data from large populations, often through questionnaires.

A case study strategy allows for an in-depth investigation of a single case or a small number of cases within their real-life context. It is particularly valuable in exploratory and explanatory research. Grounded theory aims to develop new theory directly from the data, rather than testing existing theory. It is often employed in qualitative research involving iterative coding and conceptual development.

Ethnography involves the detailed observation and participation in the cultural or social lives of research subjects, usually over an extended period. Action research engages participants collaboratively in diagnosing and solving practical problems while generating academic insights. Finally, archival research uses existing records and documents to explore historical or contemporary phenomena.

Methodological Choice: Mono, Mixed, or Multi-Method

The next layer deals with research choices, which dictate the collection and analysis of data. Researchers may choose a mono method, involving either qualitative or quantitative data, or a mixed-methods approach that integrates both. A multi-method approach, while similar to mixed methods, typically involves using multiple techniques within the same paradigm (e.g., two qualitative methods).

Mono-method designs are straightforward and easier to manage but may provide limited perspectives. In contrast, mixed-methods research allows for triangulation—where findings from different types of data complement or validate each other—thus offering a richer and more comprehensive understanding of the research problem. However, this approach demands greater resources and methodological expertise.

Time Horizon: Considering the Temporal Framework

The time horizon is another critical consideration in research design. It refers to the temporal aspect of the study and is divided into cross-sectional and longitudinal research.

Cross-sectional studies capture data at a single point. Descriptive or correlational research commonly uses them to capture a snapshot of the phenomenon under study. These studies are practical and time-efficient but may fail to account for changes over time.

In contrast, longitudinal studies involve data collection over extended periods, allowing researchers to observe developments, trends, or causal relationships. While more resource-intensive, longitudinal designs provide deeper insights into dynamic processes and are especially useful in fields like developmental psychology, organizational studies, and education.

Data Collection and Analysis Techniques: The Practical Core

The data collection and analysis techniques, which translate theoretical decisions into practical procedures, form the core of the Research Onion. This layer encompasses sampling methods, data collection instruments, and data analysis strategies.

Data collection methods vary depending on whether the research is qualitative or quantitative. For quantitative research, tools like structured questionnaires, standardized tests, and statistical databases are commonly used. For qualitative research, techniques include semi-structured interviews, focus groups, participant observations, and document analysis.

Data analysis also differs by paradigm. Quantitative data is analyzed using statistical techniques—ranging from descriptive statistics to complex inferential models—typically supported by software such as SPSS or R. Qualitative data analysis involves thematic or content analysis, where researchers identify, code, and interpret patterns and meanings in textual or visual data. Software tools like NVivo can aid this process.

Importantly, this layer also involves addressing ethical considerations, including informed consent, confidentiality, and data integrity. Researchers must adhere to institutional and disciplinary ethical guidelines to ensure the trustworthiness and credibility of their work.

Conclusion

The Research Onion provides a comprehensive, layered model for designing and conducting research in a systematic and coherent manner. By peeling back each layer—from philosophical foundations to methodological choices and data analysis—researchers can ensure that their studies are grounded in academic rigor and methodological alignment. Whether one is pursuing a deductive, positivist inquiry or an inductive, interpretivist exploration, the Research Onion serves as an invaluable framework for navigating the complexities of research methodology with clarity and purpose.

| Layer | Focus | Examples |

| Research Philosophy | Worldview | Positivism, Interpretivism |

| Research Approach | Reasoning | Deductive, Inductive |

| Research Strategy | Plan of action | Survey, Case Study |

| Research Choice | Method | Mono, Mixed |

| Time Horizon | Duration | Cross-sectional, Longitudinal |

| Techniques & Procedures | Practical steps | Interviews, Data analysis |

Readings

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2007). Research Methods for Business Students (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Melnikovas, A. (2018) ‘Towards an Explicit Research Methodology: Adapting Research Onion Model for Futures Studies,’ Journal of Futures Studies, 23(2), pp. 29–44. https://doi.org/10.6531/jfs.201812_23(2).0003.

Leave a Reply